Monroe County man part of science breakthrough

A fusion science breakthrough decades in the making took place last month, and a Monroe County native played a substantial role in what could be a big step for clean energy.

Mark Herrmann grew up in Columbia. He attended Immaculate Conception Catholic School and Gibault Catholic High School, later going to Washington University in St. Louis for his undergraduate education.

Herrmann eventually attended Princeton University, where he received the specialist education that would later lead to his role in making scientific history at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

“I work on and my PhD was in plasma physics, the study of the behavior of matter at very, very high temperatures,” Herrmann said. “It just behaves very differently at very high temperatures, so that’s the expertise that I used when I got here to study an approach to fusion called inertial confinement fusion.”

Herrmann came to Lawrence Livermore to research the conditions necessary in order to achieve a fusion reaction that would result in more energy being released by the experiment than was put into it.

In the years since, Herrmann said he has taken on more managerial positions.

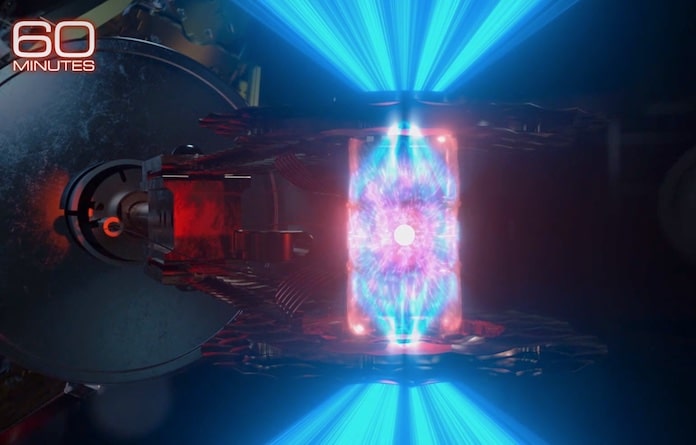

He is currently serving as program director for weapon physics and design at Lawrence Livermore, though he also previously served as director of the National Ignition Facility, the lab that houses one of the world’s most powerful lasers used in the December experiment.

Herrmann said he is currently among several individuals who oversee the research to determine how the facility gets used. A key aspect of his job is ensuring the United States’ nuclear deterrent remains “safe, secure, effective and reliable.”

This is done through research which gives a better understanding of fusion.

“We study thermonuclear fusion,” Herrmann said. “Fusion is the process that powers the sun and all the stars. It’s also the process that makes all of our modern nuclear weapons work. It requires very extreme conditions, incredibly high temperatures, 100 million degrees, above 100 million degrees, incredibly high pressure. We squeeze matter to pressures that are greater than the pressure that would be felt if you were at the center of the sun.”

As Herrmann described, fusion is the process of elements – namely hydrogen – coming together, a process which produces energy.

Fusion is a very separate process from fission, the reaction used in power plants that involves heavy elements like uranium breaking apart and releasing energy.

Experiments at the NIF focus on fusion, shooting a high-powered laser at a tiny pellet of hydrogen in order to generate a fusion reaction.

For many years, the use of that powerful laser made fusion reactions come with relative ease, but the real goal has long been a particular, far more difficult to achieve reaction.

“The search since the 1950s has been on ‘Can we devise ways in the laboratory to heat up this fusion fuel to high enough temperatures and confine it for long enough, hold it together for long enough’ – because when it gets very hot it’s very hard to hold it – ‘Can we do that in a way that we can actually get more fusion energy out than we invested into that?’” Herrmann said. “That’s been a goal for six decades.”

That goal was long thought unattainable, with thousands of individuals across the world working toward it.

The NIF director featured in a segment that aired on the CBS program “60 Minutes” on Sunday even noted nicknames the lab had been called over the years – Never-Ignition Facility among them.

An experiment last month changed all that.

As Herrmann explained, the fusion reactions taking place within the pellet of hydrogen finally occurred at a greater rate than the pellet was able to cool, resulting in a series of reactions that produced 1.5 times more energy than was used to heat the pellet.

While the actual amount of energy produced was quite small, the implications of the experiment – namely that a fusion reaction like this is actually achievable in a lab setting – are tremendous.

Since the success, the NIF’s work has received a substantial amount of attention, with much praise aimed at Herrmann and the numerous other researchers at the facility.

Back home, Herrmann’s parents were exceptionally pleased to hear about their son’s work.

“Naturally, we’re very proud of him,” Herrmann’s father Tom said. “It’s way beyond our comprehension, you know. It’s very delicate stuff they’re working on, and it really was a major breakthrough. They had been working on that so long, and when that happened they were all so excited about it. So we’re happy for them.”

Former ICS Principal Mike Kish, who is currently serving as interim principal at Gibault, also extended his congratulations to Herrmann and the NIF team for their efforts toward clean energy.

“They have proven that a dream is possible,” Kish said. “We are proud of our connection to Dr. Mark Herrmann and his part in making a better future for the world.”

Herrmann expressed his satisfaction with the facility’s efforts, emphasizing the fact this sort of fusion reaction has been a seemingly unattainable goal for decades.

“It feels really, really awesome,” Herrmann said. “It’s such a huge team with so many people on it who have worked together … all striving for this goal, this kind of marker to say ‘Yeah, we can do this.’ And there’s been a lot of ups and downs along the way with setbacks and obstacles and, frankly, people looking from the outside saying ‘You’re never gonna get there.’ And a team of people kept working on it and kept going despite the obstacles, overcoming the obstacles and ultimately achieving that goal. It feels really good. It feels like something I’ll remember for the rest of my life.”

Looking to the future, Herrmann had a tempered but hopeful outlook. While December’s results do indicate hope for the possibility of clean fusion energy, he noted there would be substantial work to do in figuring out how such a power plant would work.

The “60 Minutes” piece shared a similar sentiment, with the many factors necessary to make such power plants proving to be a major road block for fusion energy production in the near future.

Herrmann did note the more immediate benefits the reaction offers to the understanding of fusion as a process – with fusion simulations likely to be vastly improved with the reaction now reproducible in a lab setting.

The experiment’s success also serves as a major milestone for Herrmann’s work in national security, as a better understanding of nuclear fusion should better the country’s ability to maintain a nuclear deterrent.

Herrmann also expressed he and his colleagues’ desire to make the reaction happen again.

“We of course want to do it again,” Herrmann said, “over and over again because the other thing we’ve never been able to do is study these extreme conditions in the laboratory before like this, so we’re able to now repeat this experiment and also make it better.”

For those who were not able to watch Sunday’s “60 Minutes” piece, it is available online by clicking here.