A fight to preserve history

As the Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail Coalition makes clear, Monroe County and the surrounding area is rich with history, from more recent developments through the last few decades to landmarks providing residents with a view of what the region was like centuries ago.

Many locals are sure to have paid a visit to Fort de Chartres near Prairie du Rocher, with the annual Rendezvous in particular providing a snapshot of French colonialism in the area.

Traveling much farther up Bluff Road to Columbia, folks can see the site of the former Fort Piggott, and, thanks to the recent efforts of the coalition, get a glimpse into how settlers first established here.

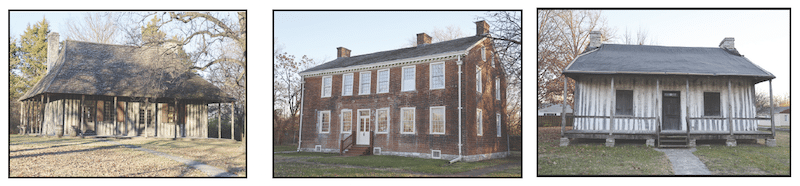

Those who continue headed north into Dupo, East Carondelet and Cahokia can learn even more about the region as they visit a trio of historic buildings that paint a vivid picture of the past even as their caretakers have struggled in recent years.

In mid-November, the Republic-Times published an article discussing one of these landmarks – the Martin-Boismenue House – with local historian and coalition member Dennis Patton sharing his perspective as the location had caught the organization’s attention given its unfortunate state of disrepair.

Soon after, local historian Andrew Cooperman, who currently works in Cahokia as part of the team maintaining and teaching about the area’s history, reached out and offered a more in-depth exploration of the house’s story as well as that of the Jarrot Mansion and Cahokia Courthouse.

As was the subject of the Martin-Boismenue House article, one of the most striking parts of these locations is how they are currently being cared for today.

While the courthouse is regularly open to the public as a small museum and the mansion is similarly available for tours, the house has been closed for years now, its steps and porch in rough shape and, much more conspicuous, its roof damaged and largely covered with a tarp to help prevent any additional weather damage.

The state of the house has hardly to do with any lack of passion from local historians like Cooperman and Brad Winn, the man who has been overseeing the Cahokia landmarks and several other locations for many years.

As Winn explained, it’s simply a matter of funding.

He said that though the team headquartered at the Cahokia Courthouse was rather robust before and during the early 2000s, over the years, funding for operation and staffing has been severely diminished.

“Those days don’t last,” Winn said. “We’re not always gonna maintain that high platform. A large amount of that happened after the bubble burst. If you recall after 9/11, there was a pretty precipitous drop in revenue statewide. We began to tighten the belt strap as far as we could. What that simply means is we still have the same kind of responsibilities, we just don’t have the same funding sources available through tax revenue or budget allocations.”

Winn further explained that the big shift came as oversight for these landmarks moved from the Illinois Preservation Society to the Illinois Historic Preservation Division of the Department of Natural Resources, a much larger agency with a need to stretch its budget over a great many parks and historic sites on top of its many other responsibilities.

In terms of impact, this decrease in available funding has led to an inability for major renovation and restoration projects as well as a steady decrease in staff as individuals who retire or step away from these St. Clair County sites simply aren’t replaced.

Perhaps one of the more concrete effects of this lack of funding and staffing shortage was seen by this reporter, who approached the Cahokia Courthouse visitor center only to be greeted by Cooperman, hurriedly calling Winn in order to fix a faucet in one of the bathrooms which had broken and was stuck running.

Even as they have been left with tremendous responsibility and very few resources, it’s clear the team overseeing these three sites have a thorough interest and passion for what they do.

Cooperman exemplified this as he recounted the remarkable history of the area.

Much of his focus went toward the old courthouse only a few yards away from the visitor center, though he emphasized the courthouse and Cahokia’s histories have much broader importance than one might think.

“We’ve been around for a very long time, and there’s a lot that has happened here, things that had an impact not just on local history or regional history but on national history,” Cooperman said.

Cahokia, he said, was the first settlement in the mid-Mississippi Valley, founded in 1699 with the courthouse being built in the 1740s as a family dwelling before becoming a courthouse decades later.

The settlement of Cahokia is old enough that residents are sure to have seen the very beginnings of St. Louis as it was being built across the river.

St. Louis and Cahokia, he added, were the sites of the westernmost conflict in the American Revolutionary War.

As far as the courthouse’s specific history, perhaps its largest claim to fame is that it – also serving as a post office – was the primary hub for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark as they prepared for their expedition to explore the Louisiana Territory.

Cooperman also recalled a story of the expedition’s return in 1806 when Lewis insisted any mail be held through the night in order for him to write a letter to President Thomas Jefferson and have it sent out immediately in the morning.

Cooperman also had plenty to say in regard to the courthouse’s construction, with its upright log walls typical of much colonial French construction.

Moving to the other site located within Cahokia, Cooperman spoke about the Jarrot Mansion, discussing both the building’s history and its connection to the end of slavery in Illinois.

While Illinois was technically a free state, he explained that certain property rights which had been maintained over the years meant slavery itself was still active within the southern part of the state, though the sale of slaves was prohibited given the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and 1818 Illinois State Constitution.

In 1845, all slaves in the state achieved their freedom with the case of Jarrot v. Jarrot in which Joseph “Pete” Jarrot sued his owner Julie Jarrot for wages.

While Cooperman said Joseph lost his case in the court in Belleville, he later won in Springfield.

Along with its connection to the state’s history of slavery, the Jarrot Mansion has a unique history of its own.

Its construction finished in 1810 the mansion was built by Nicholas Jarrot, who was born in France in 1764. He left the country before the French Revolution, living for a time in Baltimore and New Orleans before making a place for himself in Cahokia in 1793.

Nicholas was, as his mansion might suggest, very successful, with most of his business ventures focused on real estate – though he also owned a general store and several milling operations.

Cooperman noted how it was one of these milling operations that was the death of him, as he struggled to construct a mill along the river numerous times – Cooperman compared him to the king in the movie Monty Python and the Holy Grail, constantly rebuilding his castle in a swamp even as it sinks or falls apart.

As he described, Nicholas was tending to the mill in December when he fell into the water. He caught a chill which turned into a fever which took his life.

Like the courthouse, Cooperman noted the unique construction of the Jarrot Mansion, built in a brick American “federal” style to Nicholas’ specifications as those who actually constructed the building had likely never seen such a home.

The bottom floor of the house, Cooperman said, is seven courses thick, with the outer walls of the second floor standing at five layers of brick.

While the Martin-Boismenue House doesn’t have the lengthy history of the Jarrot Mansion, Cooperman was able to capture what sort of perspective it offers for what life was like in colonial Cahokia – especially when compared to its more extravagant contemporary.

While it might be quite humble to those viewing it today, the house, he explained, was for a solidly middle-class farming family.

The building consists of two rooms, one primarily serving as a bedroom and the other serving as a kitchen, dining room and general living space, though Cooperman noted that, in such a small home, there would hardly be major distinctions between what is done in what room.

The house also features a basement space underneath half the house – a vitally cool place for summer months – as well as two fireplaces.

This, as Cooperman pointed out, is substantially different from the two-story Jarrot Mansion.

“They weren’t scraping by,” Cooperman said. “They were what we today would call solid middle class. And yet the difference between the two dwellings gives you an idea of just how wealthy the Jarrots were.”

As one can imagine given how long he’s studied the subject, Cooperman spoke at great length about the Cahokia area and the trio of sites he’s been helping take care of.

He spoke about the importance of knowing and recognizing local history, though it might be easy for folks to write it off.

Cooperman himself grew up in Cahokia. He recalled starting his local historic preservation work years ago and how he’s been able to share his passion with a number of people, including his own mother.

“When I started volunteering here and working here and learning more about Cahokia, she was just gobsmacked,” Cooperman said.

He noted how folks can feel a certain sense of pride as they learn about the history of where they live.

Cooperman further described two instances where he effectively stumbled into education opportunities, once when a group of kids stumbled into the visitor center for some water only to get a major history lesson and end up bringing along some other friends for another tour.

He also mentioned the time he was doing some masonry work at the mansion when a young man passed by. The two struck up a conversation, Cooperman got into the mansion’s history relating to slavery in Illinois and the man later returned with his little sister and asked Cooperman to speak more about Cahokia history.

Cooperman summarized his feelings on local history by stressing that folks don’t need to travel far to get a sense of what life was like for Americans centuries ago.

“If you have an interest in colonial-American history, you don’t have to go to Williamsburg or Jamestown. We have it by the bucketful right here in the mid-Mississippi Valley,” Cooperman said. “It’s just our colonial history has a French accent and – across the river – a French and a Spanish one, but it’s still colonial-American history. And it’s unique. What we had here was not a cheap knock-off of what was on the East Coast. It was very unique.”

With this passion for history, however, comes the question of how to continue preserving it with tight budgets and stretched-thin staff.

Cooperman touched on this as well, saying he doesn’t begrudge legislators for having to make decisions that leave historic sites like those in Cahokia on the backburner in favor of more pressing public concerns.

Still, he outlined some of his team’s dreams for Cahokia history should they ever achieve greater funding, namely renovating the outside of the Jarrot Mansion – building a historically-accurate path to the front door lined with native flora – and finally repairing the Martin-Boismenue House and re-opening it to the public.

On this note, Winn spoke about how the sites have been preserved to this point thanks to the passion of individuals like Cooperman and groups like the Jarrot Mansion Project.

“You’ve got a very passionate community, maybe in some way small in numbers as far as individuals but you’ve got a lot of people that are what I would call pretty mighty as far as what they can accomplish,” Winn said. “We have always counted on the passion and support of our communities to protect and preserve not just our parks but our historic sites. We’re able to do a great deal with just a few.”

Winn, too, spoke about the importance of preserving history such as that found in and near Cahokia.

He spoke with some poetry, describing how individuals are the culmination of their history, and it’s the job of those working in historic preservation to help people and communities make connections to their past.

“What I find so fascinating is our ability to tell these kinds of stories and to draw these kinds of connections for people, and that’s one of the values of historic preservation,” Winn said. “If you want to appreciate and respect where you’ve come from, you need to kind of take the time to appreciate and respect what these stories and these sites have to tell us.”

For more information on the Jarrot Mansion Project, call 618-235-7628 or visit jarrotmansion.org.

For more information on the Cahokia Courthouse or Martin-Boismenue House, call 618-332-1782.